“Life meanders like a path through the woods. We have seasons when we flourish and seasons when the leaves fall from us, revealing our bare bones. Given time, they grow again.”

― Katherine May, Wintering: The power of rest and retreat in difficult times

For months I have meant to write about winter, and now it’s nearly spring.

But then, this was a winter in the truest sense: grueling, bitter, relentlessly dark. No shortcuts, no escape routes — the only way out was through. Maybe it’s best viewed in hindsight anyway, drawing back the curtains to shed light on these shapeless, endless months I’m trying to parse meaning from even still. The time has finally come to check off write a newsletter (or anything that isn’t a Notes app, really) from my mental to-do list, where it’s leered at me from high atop a teetering stack of tasks far too long. As I enter this new season, I’m trying my best to be a person who follows through, even — and maybe especially — if it’s a promise I’ve made only to myself.

Before winter, though, there was fall, when — after a year of banging my head against countless metaphorical walls — I’d finally reached my breaking point with New York. By October, I needed something, anything, to pull myself out of the self-pitying tailspin that reduced my entire world to the four walls of my apartment, where I was rendered immobile by ruminating thoughts. What I needed, desperately and urgently, was a long drive to clear my head, and a weekend to see autumn in New England before it was gone.

It was a spontaneous decision, as mine often tend to be; a loose itinerary improvised in real time, as they almost always are. I felt like I was getting away with something, like I’d pulled off a grand heist or great escape, as I carefully maneuvered my rental car out of New York City and began putting miles of interstate between us, the afternoon sun already beginning to slant earthward in long golden shafts of light flooding through the flaming corridor of trees lining the highway. I was positively giddy with my newfound freedom. I made a pit-stop for coffee in leafy, sleepy New Haven, and crossed the state line into Massachusetts just as twilight was turning the mountains and river valleys the most ethereal purple and blue. I watched that sunset as if it was the first I’d ever seen, until every last ray of light was gone.

I arrived long after dark — and many hours behind an already tenuous schedule — at a little cabin in middle-of-nowhere Vermont I’d booked earlier that day. The air was so still and the sky was so dark I swear I could almost hear the stars, blinking and quivering as if full of things to tell me. I suppose it should have made me feel small, or lonesome, all alone beneath an endless expanse of universe. But I felt larger than myself out there, felt the whole world and all my misery within it fall away. The stars didn’t need to ask where I’d been, what had taken me so long. I was there, and that was all that mattered.

I woke the next morning to a cold blue dawn, dew on the grass and mist rising over the river across from the cabin. I lucked into the most heavenly fall day for a drive to New Hampshire’s White Mountains, and from the peak of an almost entirely vertical hike I swear I could see the curvature of the earth. I basked on the rock like a lizard in the late autumn sun, wholly content, as all around me families took selfies and strangers offered to take each other’s photos and college girls cracked open celebratory cans of hard seltzer. For a few blissful moments, there was nowhere to be but there, nothing else to do but enjoy the view.

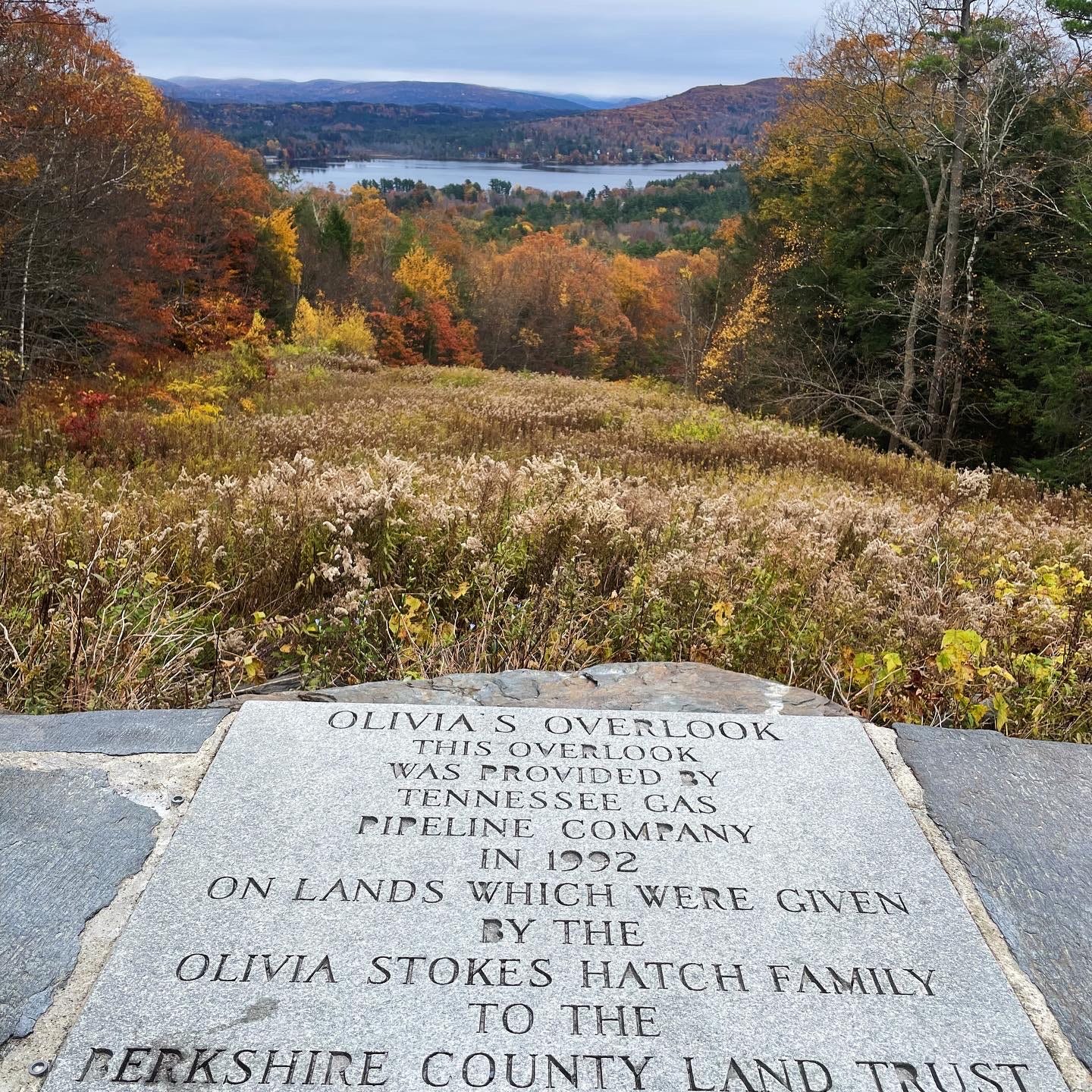

I made it back down the mountain at the tail end of golden hour, driving through the twilight to round out a pretty picture-perfect day with pizza and beer at a rustic White Mountain brewery, overlooking a river with an old covered bridge. The next day, I ate a million maple-flavored things in Stowe, Vermont, which looks more like a 19th-century oil painting than a bustling ski town, and wandered around the leafy streets of Montpelier. I spent my last night in New England at a bed-and-breakfast in the Berkshires, where I played a baby grand piano in the parlor and read about the area’s literary history with my morning coffee on the wraparound porch, surrounded on all sides by foliage blazing like a house on fire. I made small talk with the hotel’s manager, a former New Yorker who explained the buses I could probably take to get to the Berkshires from the city. I imagined myself living there, running my own bed-and-breakfast, or a quaint bookstore. I savored every last minute in those mountains, pulling over for a final view at a vista serendipitously called Olivia’s Overlook, gathering every ounce of willpower within me to start my drive back to New York.

The life I felt returning to me up there — and the little death I felt every time I thought of returning to New York — was the final push I needed to finally face the music. There was no use in delaying the inevitable, nothing to be gained from continuing down this road. I had nothing left to give, or to prove, by staying where I was unhappy.

In the weeks that followed (though many months in the making,) I quit my job, gave notice on my apartment, and pulled the plug on my life in New York. Mercifully, I’ll spare you a belabored “why I left New York” diatribe, because my experience is not particularly interesting or unique (I read an entire book of essays on the subject that greatly assuaged my self-doubt about the decision,) and because, quite simply, New York was never going to be home. Maybe someday I’ll elaborate further, but ultimately I didn’t like the life I was living, or the person I was becoming, in New York. And that was enough.

But even in my brief tenure in New York, even after everything, there was so much good, so much to be grateful for. Once-in-a-lifetime experiences, people I feel immensely lucky to have met, experiences I’d do everything over again just to have. And above all, there was growth. Growth so intense I thought my bones might shatter and my skin might shed until I woke one day to find that I was someone else entirely underneath. New York was a baptism by fire, the final breakneck sprint of growing up. There was nowhere left to hide from myself in that city; every wall a mirror, every minute a test of will. All of my flaws fluorescent-lit in stark relief, all of my illusions exposed as frauds, leaving bitter truths in their wake. New York tugged at the string that unraveled nearly everything I thought I knew about myself. It was a wake up call, shaking me by the shoulders until I could see, for perhaps the first time, how far I’d run aground from where I’d meant to be.

Of course, maybe moving to New York was only a catalyst for the tidal wave of change I’ve found myself riding at the tail end of my twenties; maybe it could have been anywhere. But I think New York was the first place that ever told me the truth. I think sometimes honesty has to break us wide open, to wake us from a dream we’ve been dreaming too long. I think maybe that’s where life really begins.

On my last night in my first New York apartment, I sat on the fire escape for a final time, reflecting on the bright mornings I’d crawled out onto the cold wrought-iron with a cup of coffee, the breezy summer evenings I’d let my feet dangle over the side while sipping a glass of wine. The books I’d read and things I’d written there. How I’d marked the passing of time by the trees in the courtyard, as they changed from verdant green to burnt orange and red before losing their leaves entirely. How the first winter, I woke one morning to find all the branches blanketed in white, how surreal it felt to watch snow fall on New York City from inside the little piece of it that was mine.

As I said silent goodbyes to my darkened apartment, light from the building across the way streamed through the branches of the trees outside, casting spindly shadows on the empty bookshelves I’d fallen in love with at first sight. I had the realization that there was once a time I didn’t know how this story ended. I had the strangest sensation that my past and present were intermingling then, that for a moment there was no past or present at all. All the hope I’d carried in there was less palpable now, but I could feel the heat of it still. And in the shadows on the wall, I could I see them clear as day; the ghosts of the things I wanted, dancing with the ghosts of the things I got. The life I envisioned, imperfectly rendered by the life I actually lived. I don’t think I’ve ever felt bittersweetness as true as that before. The flash of clarity that comes from holding in your hands both heartbreak and the truth that can only ever meet you on the other side of it. To know somehow they weigh exactly the same.

In those overwhelming final weeks in New York, one of the strongest forces keeping me afloat was the promise of returning to the Pacific Northwest. I wanted nothing more than to feel the wind on my face as I stood on some rugged coastline, surrounded by snowcapped mountains and emerald trees. And so, after a brief detour at my parents’ house (mostly due to finally being felled by COVID after nearly three years,) I packed up my car and headed up to Washington at the end of January. I’d been lucky enough to score a three-week house sit on a small, remote island just above the San Juans, so far north you can drive to Canada for the afternoon. I’d been a little hesitant that the location might be too isolated, but looking back now, ending up there feels a little like fate.

The house was situated in a private cove, and most mornings I walked down to the shore as the sun rose in a bright flood of gold over Mt. Baker, meditating among the driftwood and scouring the beach for whatever new sea glass and shells the tide had brought in. One morning I woke to find that it had snowed overnight, dusting the trees and rocky beaches in a fine powder. On gloomy days, the cove became socked in with fog, and silver mist descended upon the towering tree line in the late afternoon. On clear days, the most brilliant orange and pink sunsets swirled across the sky and turned the San Juan Islands indigo just across the archipelago. The nights were so dark that you could see star clusters, entire constellations, the red tinge of Mars. In early February, the full Wolf Moon rose so brightly over the cove that it could have been the sun. Once night it hovered directly above the skylight in my bedroom, creating a perfect rectangle of moonlight on the floor.

Those were weeks of magic, and I did my best to savor every single moment of it. I went days without opening social media, or seeing other people, and spent my nights curled up with cats and books, listening to the wind howling, the rain tapping on the skylights, an owl hooting from somewhere in the towering firs outside my door. The emotional and physical toll of the move, followed by COVID, had left me feeling like a husk of myself, and all I wanted was to withdraw from the world and retreat inward. I was suddenly fiercely protective of my privacy and personal space, of my need to rest and process, to heal and lick my wounds, to sort through all the noise and hopefully find some clarity in the quiet.

Without even realizing it, I was, as the author Katherine May defines it, Wintering:

“Doing those deeply unfashionable things—slowing down, letting your spare time expand, getting enough sleep, resting—is a radical act now, but it is essential. This is a crossroads we all know, a moment when you need to shed a skin. If you do, you’ll expose all those painful nerve endings and feel so raw that you’ll need to take care of yourself for a while. If you don’t, then that skin will harden around you.”

― Katherine May, Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times

I missed those days and nights even as I was living them; the solitude, the silence, the promise that each day, if nothing else, the sun would rise, the tide would fall, the stars would appear at night. I was overwhelmed with gratitude, ravenous for the present moment, so fortunate to have this chance to return to stillness, to centeredness, feeling so far from the world and yet never more entwined with it. I would have stayed there forever if I could.

But that’s the thing about wintering: there’s an end date, however loose. However long it takes for winter to melt and thaw and relinquish its hold to give way to something new, until slowly but surely the days become longer, the sun becomes brighter. Until life begins again. It is cyclical, it is promised, even though in the depths of winter it feels impossible to imagine. And so here we are. Here I am. Standing at the edge of the forest, the doldrums of winter, the first signs of spring. It is both an astonishing surprise and the most expected thing in the world. That even after disappointment and loss and depths we are certain we won’t survive, life persists. That even after mistakes, we are forgiven. Even after darkness, the sun returns. And we get the chance to try again.

I’ve just started Katherine May’s follow-up to Wintering, which is called Enchantment and is in essence about how to feel alive again. It’s the perfect companion for moving into spring, a call to reawaken the heart and soul after bitter darkness and cold. And it feels as personally timely to me as Wintering, as I find myself frayed from months of simply surviving, trying to remember how to do more than that again.

I don’t know what comes after this, other than — as always — spring, and then summer, and fall. I’ll turn thirty then, something that is both unimaginable and exhilarating to think about, and there are so many things I want to set in motion this year, and so many things I want to leave behind in this decade, too.

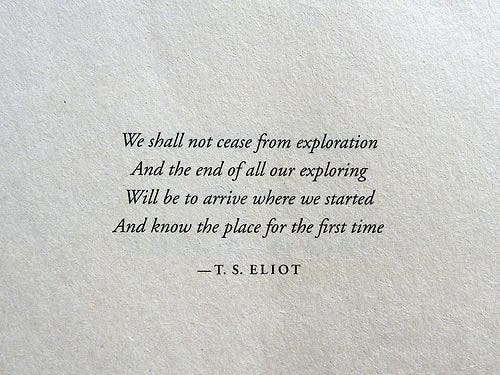

Some days it feels as though time is only spinning faster, that the gap between me and the life I want is only growing wider, and every decision I make seemingly in its favor only sets me one step forward and fifty steps back. Sometimes it feels like I’ve been through hell only to end up exactly where I started again. And yet, as spring begins to bloom and these cycles continue as they always do, I’m reminded that “coming back to where you started is not the same as never leaving.” Sometimes we must go away in order to come back, must lose the things we want to find the things we need, must live through winter to ever really feel spring.